Before I begin, I’ll flag this as under ‘food for thought’. It’s a complex topic, and I’d very much like to address it more in future. But for now, let’s take a brief look at The Unlikeables.

Warning: contains spoilers for Breaking Bad, There Will Be Blood and Nightcrawler.

I’ve often heard the comment “I couldn’t keep watching it, because I didn’t like any of the characters.” I’ve said it myself, erroneously.

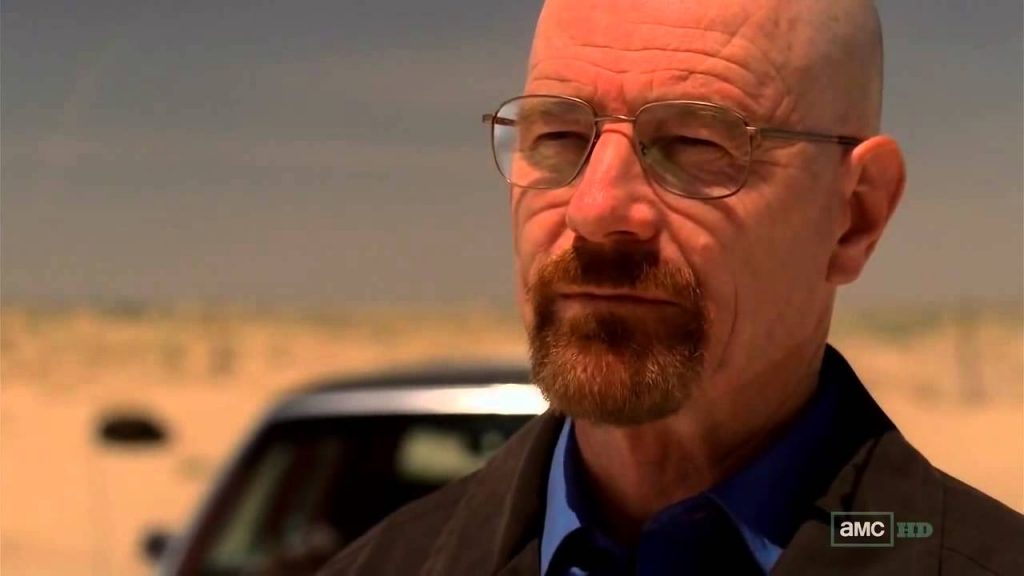

Character likeability is frequently how we express the reason why we’re invested in a character. But we don’t need to like our protagonists, do we? Did you really like Walter White?

In Breaking Bad Walter’s motives are, by the end of Season 1, transparent, but denied until the end of the series finale: he likes it. What starts as a desperate attempt to leave his children financial security when he dies from lung cancer quickly becomes an entirely selfish enterprise he could cease at any time, especially when he enters remission.

But, as the writers establish in the first episode of the series, the show is a “study of change”. We watch an array of interesting, incredibly flawed characters come undone.

We might watch to satisfy the appetites of our power fantasies, or because we’re addicted to seeing how Walter gets out of a bind. Maybe it’s the hope Hank will triumph that keeps us going.

I would say it is, least of all, about likeability.

My favourite film, There Will Be Blood is another example. Daniel Plainview — a 19th Century oil man — might be a marvellous entrepreneur, but his methods and near-absent humanity aren’t admirable. His goal, after all, is to satisfy his misanthropic desires and build a place where he can hide from humanity.

His efforts are frustrated by a mirror: an evangelical minister who is amassing wealth by, in Daniel’s estimation, cynically abusing the faith of poor people. Eli.

And to get his way, Daniel is willing to appease Eli, and the god neither truly believe in, to access land for an oil pipeline. He’ll kill to accomplish his goals.

I haven’t even mentioned the abandonment of his adopted son, who is made deaf by an oil explosion and becomes too troublesome for Plainview to keep around. In later years he tells his son he only kept him around to create a ‘family business’ brand — Daniel lacks the softness to connect with people, and so used the boy. While he says this in anger, and I believe it is at least in part a lie, we know there is an element of truth. I believe he saved the orphan out of genuine kindness, but did frequently use him as an asset. It isn’t that he doesn’t love, it’s that the drive to achieve his objective is stronger.

Daniel is not a nice person. He isn’t likeable. As a businessman he is ruthless, but admirable. As a father he is cruel, but loving — however fleeting his expressions may be. For me he is addictive to watch, because we see him begin as a lone man in a pit who manages to build — slowly — an empire. And however flawed, however hypocritical, he has a staunch opposition to the use of religion to manipulate people. He despises his nemesis, Eli — and Eli is deserving of all our condemnation.

Nightcrawler is another example I’ll touch on briefly. Louis Bloom is, basically, a psychopath. He is a single-minded, manipulative, calculating man with no interest in the needs or wants of others beyond their factoring into his goals. Louis will kill people to reach his aspirations. He wants to be successful. That is, really, about it. Once he finds a path that matches his personality, we watch him become unstoppable in his field. He becomes a freelance gore videographer, who films murder scenes, accidents and disasters and sells the footage to news channels so they can feed the world’s insatiable appetite for horrific imagery.

In a field where ethics are a distant speck in the rear-view, an unethical person can thrive.

And yet, like Walter White and Daniel Plainview, he is incredibly watchable.

So when we say likeable I think we really mean watchable. And what makes a character watchable is far more complex, and vastly less difficult to achieve when the character is likeable. If we like the character the gap between them and the audience is, in my opinion, far smaller. If characters are unlikeable I feel we arrive, far sooner, at ‘why am I watching this character?’

This is behind the black and white nature of mainstream cinema. Even when there is ambiguity or ‘oooo, Batman is fighting Superman!’ we often see incredible shortcuts to resolving the problem. I think this has been very evident in the Marvel series, where almost everything is simplified to ‘destroy the world’ vs ‘save the world’ — where goals could be far more complex. Unlikeable characters don’t work in a universe designed for mass, streamlined appeal. The Dark Knight is an example of addressing more complex goals with a flawed hero and an irrational villain. The Joker wants chaos — with none of the monetary traditional benefits — and to be the twisted reflection of an already twisted hero. Forever.

Christopher Nolan wasn’t worried about portraying Batman as a man willing to subscribe to ends justifying the means. That’s why he violated the privacy of the entire city in order to save it. It’s why he became a vigilante. He’s not, simply, just a good guy.

We watch characters who don’t deserve to win, all the time. People we couldn’t imagine supporting on any level achieve their goals. It’s nothing to do with likeability. It’s about rhythms of drama. It’s about how goals are achieved, and against what obstacles. It’s hard work, and unlikable characters make it harder.

Joshua Lundberg is a Writer and Director at Barking Mouse®, and co-Founder along with Producer Georgia Woodward. Together they create films, web series as well as commercial and corporate content for clients.